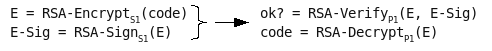

Previously, I described a proposed system that will both sign and encrypt code updates using an RSA private key. The goal is to derive the corresponding public key even though it is kept securely within the device.

If you delve into the details of RSA, the public key is the exponent and modulus pair (e, n) and private key is (d, n). The modulus is shared between the two keys and e is almost always 3, 17, or 65537. So in the vendor’s system, only d and n are actually secrets. If we could figure out d, we’ve broken RSA, so that’s likely a dead-end. But if we figure out e and n, we can decrypt the updates.

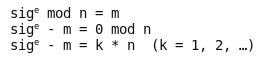

Let’s see how to efficiently figure out n using guesses of e and a pair of encrypted updates. The signature verification process, RSA-Verify, can be represented by the standard equation shown below in various forms.

The first step is the standard RSA-Pub-Op and the result is m, the padded hash of the message. The remaining steps in RSA-Verify (i.e., validating the signature) are not relevant to this attack. In the second equation, m is refactored to the left side. Finally, 0 mod n is described in an alternate form as k * n. The particular k value is the number of times the odometer has wrapped during exponentiation. It’s not important to us, just the modulus n.

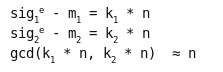

Now, assume we’ve seen two updates and their signatures, sig1 and sig2. We can convert them to the above form by raising each signature to a guess for e and subtracting the associated message m. Note that m is still encrypted and we don’t know its contents.

This gives us two values with n as the common factor. The GCD algorithm gives us the common factors of two values very quickly. The reason there is no “=” sign above is that we actually get n times some small prime factors, not just n. Those can easily be removed by trial division by primes up to 1000 since the real factors of n (p and q) are at least 100-digit numbers. Once we have n, we can take each encrypted message and decrypt it with me mod n as usual, giving us the plaintext code updates.

I implemented this attack in python for small values of e. Try it out and let me know what you think.

Doing this attack with e = 65537 is difficult due to the fact that it would have to work with values millions of bits long. However, it is feasible and was implemented by Jaffe and Kocher in 1997 using an interesting FFT-multiply method. Perhaps they will publish it at some point. Thanks go to them for explaining this attack to me a few years ago.

Finally, I’d like to reiterate what I’ve said before. Public key cryptosystems and RSA in particular are extremely fragile. Do not use them differently than they were designed. Better yet, seek expert review or design assistance when working with any design involving crypto.