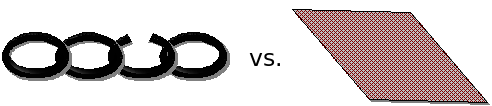

When explaining the desired properties of a security system, I often use the metaphor of a mesh versus a chain. A mesh implies many interdependent checks, protection measures, and stopgaps. A chain implies a long sequence of independent checks, each assuming or relying on the results of the others.

With a mesh, it’s clear that if you cut one or more links, your security still holds. With a chain, any time a single link is cut, the whole chain fails. Unfortunately, since it’s easier to design with the chain metaphor, most systems never last when individual assumptions begin to fail. There are surprisingly few systems that are designed with the mesh model, despite it clearly being stronger.

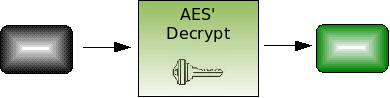

An example of a chain design is SSL accelerators that implement “split termination.” In this system, the server’s private key is moved to a middle box that decrypts the SSL session, load balances it or modifies it in some way, and then re-encrypts the data with the server’s public key and delivers it.

There are a number of weaknesses in this design beyond the obvious one that the data is in the clear while being processed by the SSL appliance. If you keep your private key in an HSM, you’ve just downgraded its security to “stored in flash and RAM of a front-end network device.” Also, now there are two places to compromise the key. Even if both offered equal security but different implementations (i.e., different bugs), you’ve reduced the private key’s security by 50% because an attacker can choose between the two targets based on their bag of exploits. But obviously, they do not offer equal security since most network devices do not include an HSM for cost reasons.

Another weakness is insertion or downgrade attacks. Insertion attacks involve the attacker connecting to the middle box and sending data to the server. The SSL appliance happily encrypts the data and delivers it to the server. If your fraud-prevention software checks for potentially phished connections by checking SSL parameters, the middle box just lied to it about the original level of security. Because the fraud prevention application’s original assumption that the other endpoint is a client was violated, it no longer can say anything meaningful about the client’s SSL connection. A downgrade attack is similar in that SSL v2 (which had trivial flaws) might be allowed on the client side but this wouldn’t show up in the connection on the server side.

The long chain of independent links introduces many potential or actual flaws. Each link has to be checked for each flaw that exists (m * n), and a failure of any link fully compromises the data.

An example of a mesh design is TLS/SSLv3 session key derivation. The two aspects that are particulary nice are the cipher downgrade prevention and combined HMAC algorithm. In SSLv2, the per-session cipher could be downgraded by a man-in-the-middle. When each side advertised its crypto capabilities, he could lie to both, saying that neither one had anything very strong and neither side could detect that this occurred. Each message in the protocol was like a link in the chain, depending on the values of the previous ones without any way to verify the previous messages hadn’t been tampered with.

SSLv3 changed this by making each side hash all the messages it had seen and use the hash as part of the generated session key. If an attacker deleted or modified messages (i.e., to reduce the advertised list of ciphers to the weakest possible), the session key for one or both sides would be incorrect. This would be detected when the Finished message was received and then both would drop the connection or try again.

The hashing primitive used for deriving keys in SSLv3 is a bit strange. It is similar to the modern HMAC construction but uses two separate hash functions, MD5 and SHA-1. At the time, this seemed insane since an attacker would have to perform a pre-image attack (even harder than a collision attack) against the hash function to find a result that would allow him to insert or modify handshake messages. Paul Kocher, the author of SSLv3, chose to use an HMAC that combined two different hash functions so that an attacker would have to find a pre-image for both. This seemed like it was going too far, increasing complexity in an area that was already quite safe. Implementers also complained at having to include two hash functions.

When the collision in MD5 and then an expected collision in SHA-1 appeared a few years ago, it didn’t seem so crazy although SSLv3 would still be secure even if it only used one hash function. I recently asked Paul why he was so focused on hash functions back in 1996 and he said, “I just didn’t trust them. MD5 hadn’t had much scrutiny and SHA-1 was brand new. So I took a conservative approach.” Of course, the genius is in knowing where it is most necessary to apply mesh principles to a design.