During the C64 and Apple II years, a number of interesting protection schemes were developed that still have parallels in today’s systems. The C64/1541 disk drive schemes relied on cleverly exploiting hardware behavior since there was no security processor onboard to use as a root of trust. Nowadays, games or DRM systems for the PC still have the same limitation, while modern video game systems rely more on custom hardware capabilities.

Most targeted anti-debugger techniques rely on exploiting shared resources. For example, a single interrupt vector cannot be used by both the application and the debugger at the same time. Reusing that resource as part of the protection scheme and for normal application operations forces the attacker to modify some other shared resource (perhaps by hooking the function prologue) instead.

One interesting anti-debugger technique was to load the computer’s protection code into screen memory. This range of RAM, as with modern integrated video chipsets, is regular system memory that is also mapped to the display chip. Writing values to this region changes the display. Reading it returns the pixel data that is onscreen. Since it’s just RAM, the CPU can execute out of it as well but the user would see garbage on the screen. The protection code would change the foreground and background colors to be the same, making the data invisible while the code executed.

When an attacker broke into program execution with a machine language monitor (i.e., debugger), the command prompt displayed by the monitor would overwrite the protection code. If it was later resumed, the program would just crash because the critical protection code was no longer present in RAM. The video memory was a shared resource used by both the protection and the debugger.

Another technique was to load code into an area of RAM that was cleared during system reset. If an attacker reset the machine without powering it off, the data would ordinarily still be present in RAM. However, if it was within a region that was zeroed by the reset code in ROM, nothing would remain for the attacker to examine.

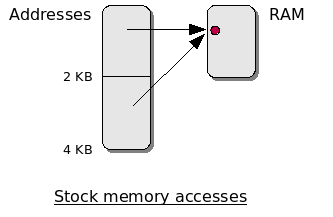

As protection schemes became stronger in the late 1980’s, users resorted to hardware-based attacks when software-only copying was no longer possible. Many protection schemes took advantage of the limited RAM in the 1541 drive (2 KB) by using custom bit encoding on the media and booting a custom loader/protection routine into the drive RAM to read it. The loader would lock out all access by the C64 to drive memory so it could not easily be dumped and analyzed.

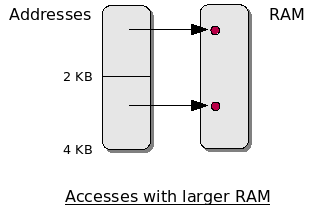

The copy system authors responded in a number of ways. One of them was to provide a RAM expansion board (8 KB) that allowed the custom bit encoding to be read all in one chunk, circumventing the boundary problems that occurred when copying in 2 KB chunks and trying to stitch them back together. It also allowed the protection code in the drive to be copied up to higher memory, saving it from being zeroed when the drive was reset. This way the drive would once again allow memory access by the C64 and the loader could be dumped and analyzed.

Protection authors responded by crashing the drive when expanded RAM was present. With most hardware memory access, there’s a concept known as “mirroring.” If the address space is bigger than the physical RAM present, accesses to higher addresses wrap around within the actual memory. For example, accesses to address 0, 2 KB and 4 KB would map to the same RAM address (0) on a 1541 with stock memory. But on a drive with 8 KB expanded RAM, these would map to three different locations.

One technique was to scramble the latter part of the loader. The first part would descramble the remainder but use addresses above 2 KB to do its work. On a stock 1541, the memory accesses would wrap around, descrambling the proper locations in the loader. On a modified drive, they would just write garbage to upper memory and the loader would crash once it got to the still-scrambled code in the lower 2 KB.

These schemes were later circumvented by adding a switch to the RAM expansion that allowed it to be switched off when it wasn’t in use, but this did add to the annoyance factor of regularly using a modified drive.