The first step in understanding glitch attacks is to look at how hardware actually works. Each chip is made up of transistors that are combined to produce gates and then high-level features like RAM, logic, lookup tables, state machines, etc. In turn, those features are combined to produce a CPU, video decoder, coprocessor, etc. We’re most interested in secure CPUs and the computations they perform.

Each of the feature blocks on a chip are coordinated by a global clock signal. Each time it “ticks”, signals propagate from one step to another and among the various blocks. The speed of propagation is based on the chip’s architecture and physical silicon process, which together determine how quickly the main clock can run. This is why every CPU has a maximum (but not minimum) megahertz rating.

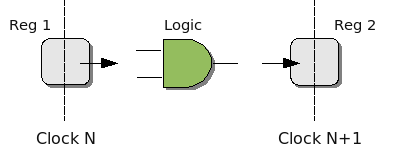

In hardware design, the logic blocks are made up of multiple stages, very much like CPU pipelining. Each clock cycle, data is read from an internal register, passes through some combinational logic, and is stored in a register to wait for the next clock cycle. The register can be the same one (i.e. for repeated processing as in multiple rounds of a block cipher) or a different one.

The maximum clock rate for the chip is constrained by the slowest block. If it takes one block 10 ns to propagate a signal from register to register, your maximum clock rate is 100 MHz, even if most of the other blocks are faster. If this is the case, the designer can either slice that function up into smaller blocks (but increase the total latency) or try to redesign it to take less time.

A CPU is made up of multiple blocks. There is logic like the ALU or branch prediction, RAM for named registers and cache, and state machines for coordinating the whole show. If you examine an assembly instruction datasheet, you’ll find that each instruction takes one or more clocks and sometimes a variable number. For example, branch instructions often take more clock cycles if the branch is taken or if there is a branch predictor and it got it wrong. As signals propagate between each block, the CPU is in an intermediate state. At a higher level, it is also in an intermediate state during execution of multi-cycle instructions.

As you can see from all this, a CPU is very sensitive to all the signals that pass through it and their timing. These signals can be influenced by the voltage at external pins, especially the clock signal since it is distributed to every block on a chip. When signals that have out-of-spec timing or voltage are applied to the pins, computation can be corrupted in surprisingly useful ways.