News and details of the first iPhone bootloader hack appeared today. My analysis of the publicly-available details released by the iPhone Dev Team is that this has nothing to do with a possible new version of the iPhone, contrary to Slashdot. It involves exploiting low-level software, not the new SDK. It is a good example how systems built from a series of links in a chain are brittle. Small modifications (in this case, a patch of a few bytes) can compromise this kind of design, and it’s hard to verify that all links have no such flaws.

A brief disclaimer: I don’t own an iPhone nor have I seen all the details of the attack. So my summary may be incomplete, although the basic principles should be applicable. My analysis is also completely based on published details, so I apologize for any inaccuracies.

For those who are new to the iPhone architecture, here’s a brief recap of what hackers have found and published. The iPhone has two CPUs of interest, the main ARM11 applications processor and an Infineon GSM processor. Most hacks up until now have involved compromising applications running on the main CPU to load code (aka “jailbreak”). Then, using that vantage point, the attacker will run a flash utility (say, “bbupdater”) to patch the GSM CPU to ignore the type of SIM installed and unlock the phone to run on other networks.

As holes have been found in the usermode application software, Apple has released firmware updates that patch them. This latest attack is a pretty big advance in that now a software attack can fully compromise the bootloader, which provides lower-level control and may be harder to patch.

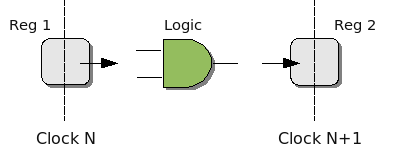

The iPhone boot sequence, according to public docs, is as follows. The ARM CPU begins executing a secure bootloader (probably in ROM) on power-up. It then starts a low-level bootloader (“LLB”), which then runs the main bootloader, “iBoot”. The iBoot loader starts the OSX kernel, which then launches the familiar Unix usermode environment. This appears to be a traditional chain-of-trust model, where each element verifies the next element is trusted and then launches it.

Once one link of this chain is compromised, it can fully control all the links that follow it. Additionally, since developers may assume all links of the chain are trusted, they may not protect upstream elements from potentially malicious downstream ones. For example, the secure bootloader might not protect against malicious input from iBoot if part or all of it remains active after iBoot is launched.

This new attack takes advantage of two properties of the bootloader system. The first is that NOR flash is trusted implicitly. The other is that there appears to be an unauthenticated system for patching the secure bootloader.

There are two kinds of flash in the iPhone: NOR and NAND. Each has different properties useful to embedded designers. NOR flash is byte-addressable and thus can be directly executed. However, it is more costly and so usually much smaller than NAND. NAND flash must be accessed via a complicated series of steps and only in page-size chunks. However, it is much cheaper to manufacture in bulk, and so is used as the 4 or 8 GB main storage in the iPhone. The NOR flash is apparently used as a kind of cache for applications.

The first problem is that software in the NOR flash is apparently unsigned. In fact, the associated signature is discarded as verified software is written to flash. So if an attacker can get access to the flash chip pins, he can just store unsigned applications there directly. However, this requires opening up the iPhone and so a software-only attack is more desirable. If there is some way to get an unsigned application copied to NOR flash, then it is indistinguishable from a properly verified app and will be run by trusted software.

The second problem is that there is a way to patch parts of the secure bootloader before iBoot uses them. It seems that the secure bootloader acts as a library for iBoot, providing an API for verifying signatures on applications. During initialization, iBoot copies the secure bootloader to RAM and then performs a series of fix-ups for function pointers that redirect back into iBoot itself. This is a standard procedure for embedded systems that work with different versions of software. Just like in Windows when imports in a PE header are rebased, iBoot has a table of offsets and byte patches it applies to the secure bootloader before calling it. This allows a single version of the secure bootloader in ROM to be used with ever-changing iBoot revisions since iBoot has the intelligence to “fix up” the library before using it.

The hackers have taken advantage of this table to add their own patches. In this case, the patch is to disable the “is RSA signature correct?” portion of the code in the bootloader library after it’s been copied to RAM. This means that the function will now always return OK, no matter what the signature actually is.

There are a number of ways this attack could have been prevented. The first is to use a mesh-based design instead of a chain with a long series of links. This would be a major paradigm shift, but additional upstream and downstream integrity checks could have found that the secure bootloader had been modified and was thus untrustworthy. This would also catch attackers if they used other means to modify the bootloader execution, say by glitching the CPU as it executed.

A simpler patch would be to include self-tests to be sure everything is working. For example, checking a random, known-bad signature at various times during execution would reveal that the signature verification routine had been modified. This would create multiple points that would need to be found and patched out by an attacker, reducing the likelihood that a single, well-located glitch is sufficient to bypass signature checking. This is another concrete example of applying mesh principles to security design.

Hackers are claiming there’s little or nothing Apple can do to counter this attack. It will be interesting to watch this as it develops and see if Apple comes up with a clever response.

Finally, if you find this kind of thing fascinating, be sure to come to my talk “Designing and Attacking DRM” at RSA 2008. I’ll be there all week so make sure to say “hi” if you will be also.