The first notable attack on SSL 3.0 was Bleichenbacher’s PKCS#1 padding attack (1998). This gave the astonishing result that any possible side channel that gave information about the result of the RSA decryption could be used to iteratively decrypt bits of a previous session key exchange. This was recently applied to an attack on the version information added to the PKCS#1 padding in SSL 3.0.

The fix to these attacks is to substitute random data for the PremasterSecret and continue the handshake if the RSA decryption result fails any validity check. This will cause the server and client to calculate different MasterSecret values, which will be detected in the encrypted Finished message and result in an error. (If you need a refresher on the SSL/TLS protocol, see this presentation.)

Note that this approach still leaves a very slight timing channel since the failure path calls the PRNG. For example, the initial padding bytes in the result would be checked and a flag set if they are invalid. But that check involves a compare and conditional branch so technically there’s still a small leak. It’s hard to eliminate all side channels, so countermeasures to them need to be carefully evaluated.

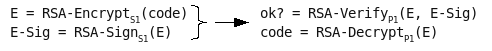

The attack is quite clever and illustrates RSA’s malleability that I wrote about in this earlier series of articles (with Thomas Ptacek). It involves successive approximation, zeroing in on the value of the plaintext message M by sending variants of the ciphertext (C) to the server. The server decrypts each message and reports “padding incorrect” or continues processing. Remember, this oracle doesn’t have to explicitly report an error message, although that’s the most obvious way to distinguish the decryption result. It could just be a timing difference.

If the server does not report “padding incorrect”, then the attacker knows that the decryption result had the proper PKCS#1 padding (e.g., starts with the bytes ’00 02′ among other things) even though the remaining bytes are incorrect. If these bytes were uncorrelated to the other bytes in the message, this wouldn’t be useful to an attacker. For example, it’s easy to create a ciphertext that AES decrypts to a value with ’00 02′ for the first two bytes but this doesn’t tell you anything about the remaining bytes. However, RSA is based on an algebraic primitive (modular exponentiation) and thus does reveal a small amount of information about the remaining bytes, which are the message the attacker is trying to guess. In fact, an early finding about RSA is that an attacker who can predict the least-significant bit of the plaintext can decrypt the entire message.

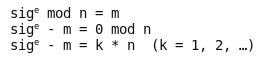

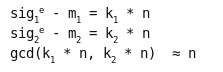

The first step of the attack is to create a number of variants of the ciphertext, which is c = me mod n. These are all of the form c’ = cse mod n, where s is a random number. Once this is decrypted by raising it to d (the private exponent), the s value can be masked off by multiplying it by s-1. This property is used in blinding to prevent timing attacks.

The second step is to send these values to the server. It decrypts each one and reports a “padding incorrect” error or success (but with a garbage result). For the s values that result in correct padding (’00 02′), the attacker knows the most-significant bit of the result is 0. In the paper, Bleichenbacher refers to this case as 2B <= ms mod n < 3B, which gives an interval of possible values for the message m. As more and smaller s values are found that are PKCS conforming, the number of possible intervals is reduced to one. That is, the union of all conforming msi values eliminates false intervals until only one is left, the one that contains the desired plaintext message.

The third step is to increase the size of the si values until they confine the message m to a single value. At that point, the original plaintext message has been found (after stripping off the given si value).

While this is a brilliant attack with far-reaching implications, it also illustrates the fragility of algebraic cryptography (i.e., public key) when subjected to seemingly insignificant implementation decisions. What engineer would think reporting an error condition was a bad thing?