I recently found a security flaw in the Google Keyczar crypto library. The impact was that an attacker could forge signatures for data that was “signed” with the SHA-1 HMAC algorithm (the default algorithm).

Firstly, I’m really glad to see more high-level libraries being developed so that programmers don’t have to work directly with algorithms. Keyczar is definitely a step in the right direction. Thanks to all the people who developed it. Also, thanks to Stephen Weis for responding quickly to address this issue after I notified him (Python fix and Java fix).

The problem was that the HMAC verify function (Python src/keyczar/keys.py, Java src/org/keyczar/HmacKey.java) leaked timing information based on how long a verify operation took to fail. The function was defined as follows for the HMAC mode:

Python

return self.Sign(msg) == sig_bytes

Java

return Arrays.equals(hmac.doFinal(), sigBytes);

Since the return value is a SHA-1 hash string, the operation devolves to a byte-by-byte compare against sig_bytes. In both Python and Java, this is a classic sequence comparison that terminates early once an incorrect match is found. This allows an attacker to iteratively try various HMAC values and see how long it takes the server to respond. The longer it takes, the more characters he has correct.

It may be non-intuitive, but the symmetric nature of MACs means the correct MAC value for an arbitrary message is a secret on-par with key material. If the attacker knows the correct MAC for a message of his choosing, he can then send that value to forge authentication of the message to the server.

I’ve implemented a simple test server using the Python version of Keyczar. It verifies an HMAC and sends back “yes” or “no” if the value is correct. I then wrote a client in C that connects to the server and tries various values for the HMAC. It tries each value multiple times and records a set of TSC differences for each. These can be fed to a program like ministat to decide when a significant difference has been confirmed (based on mean and standard deviation).

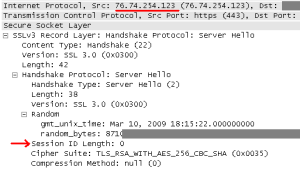

I can confirm that localhost tests have a discernible difference, depending on whether each subsequent byte is correct. I have not optimized the attack to work over a LAN or the Internet yet. However, this does not mean remote attacks are infeasible. Where jitter and other noise is present in the samples, an attacker just needs to collect more data to average it out. Remote timing attacks on SSL have been demonstrated where the timing difference was only a few native multiplies.

I recommended changing the verify function to use a timing-independent compare, such as the following.

correctMac = self.Sign(msg)

if len(correctMac) != len(sig_bytes):

return False

result = 0

for x, y in zip(correctMac, sig_bytes):

result |= ord(x) ^ ord(y)

return result == 0

This function is data-independent, except for revealing the total length of the correctMac string. Since this is not considered important to security, it is acceptable. Of course, this might not be true for another use of this same code, so it cannot be blindly used in other applications.

The lesson from this is that crypto flaws can be very subtle, especially when it comes to transitioning from an abstract concept (“compare”) to a concrete implementation (“loop while bytes are equal”). Keyczar was implemented by some smart people. If you’re a programmer, you should be using a high-level library like Keyczar or GPGME to take advantage of this knowledge. If you ignore this and develop your own design, it’s likely it would have many worse problems than this one. For those that have to build crypto, please get a third-party review of your design.

I consider it a failing of the crypto community that these libraries are still so new, while the past 20 years we’ve focused on providing raw algorithm APIs. But at least now we have a chance to build out a few important high-level libraries, review them carefully, and encourage application developers to use them. It’s not too late.