Previously, I described a recent attack on TPMs that only requires a short piece of wire. Dartmouth researchers used it to reset the TPM and then insert known-good hashes in the TPM’s PCRs. The TPM version 1.2 spec has changes to address such simple hardware attacks.

It takes a bit of work to piece together the 1.2 changes since they aren’t all in one spec. The TPM 1.2 changes spec introduces the concept of “locality”, the LPC 1.1 spec describes new firmware messages, and other information available from Google show how it all fits together.

In the TPM 1.1 spec, the PCRs were reset when the TPM was reset, and software could write to them on a “first come, first served” basis. However, in the 1.2 spec, setting certain PCRs requires a new locality message. Locality 4 is only active in a special hardware mode. This special hardware mode corresponds in the PC architecture to the SENTER instruction.

Intel SMX (now “TXT”, formerly “LT”) adds a new instruction called SENTER. AMD has a similiar instruction called SKINIT. This instruction performs the following steps:

- Load a module into RAM (usually stored in the BIOS)

- Lock it into cache

- Verify its signature

- Hash the module into a PCR at locality 4

- Enable certain new chipset registers

- Begin executing it

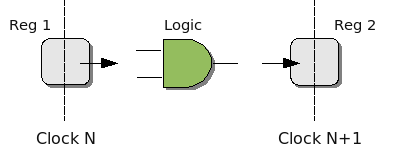

This authenticated code (AC) module then hashes the OS boot loader into a PCR at locality 3, disables the special chipset registers, and continues the boot sequence. Each time the locality level is lowered, it can’t be raised again. This means the AC module can’t overwrite the locality 4 hash and the boot loader can’t overwrite the locality 3 hash.

Locality is implemented in hardware by the chipset using the new LPC firmware commands to encapsulate messages to the TPM. Version 1.1 chipsets will not send those commands. However, a man-in-the-middle device can be built with a simple microcontroller attached to the LPC bus. While more complex than a single wire, it’s well within range of modchip manufacturers.

This microcontroller would be attached to the clock, frame, and 4-bit address/data bus, 6 lines in total. While the LPC bus is idle, this device could drive the frame and A/D lines to insert a locality 4 “reset PCR” message. Malicious software could then load whatever value it wanted into the PCRs. No one has implemented this attack as far as I know, but it has been discussed numerous times.

What is the TCG going to do about this? Probably nothing. Hardware attacks are outside their scope, at least according to their documents.

“The commands that the trusted process sends to the TPM are the normal TPM commands with a modifier that indicates that the trusted process initiated the command… The assumption is that spoofing the modifier to the TPM requires more than just a simple hardware attack, but would require expertise and possibly special hardware.”

— Proof of Locality (section 16)

This shows why drawing an arbitrary attack profile and excluding anything that is outside it often fails. Too often, the list of excluded attacks does not realistically match the value of the protected data or underestimates the cost to attackers.

In the designers’ defense, any effort to add tamper-resistance to a PC is likely to fall short. There are too many interfaces, chips, manufacturers, and use cases involved. In a closed environment like a set-top box, security can be designed to match the only intended use for the hardware. With a PC, legacy support is very important and no single party owns the platform, despite the desires of some companies.

It will be interesting to see how TCPA companies respond to the inevitable modchips, if at all.