Now that we’ve prevented casual copying using media binding, the next step is to protect the protection code itself. This is the largest and hardest task in software protection and is typically why most attackers first try to separate the prize (video/audio or software functionality) from the protection code.

The first two techniques we’ll consider are obfuscation and code encryption.

- Obfuscation uses non-standard combinations of data/code to make it difficult for an attacker (or attack software) to understand or target specific components of the software in order to compromise them

- Encryption uses cryptography (often block ciphers) to prevent the data/code from being analyzed without first obtaining the key necessary to decrypt it

Obfuscation techniques include misleading symbol names, linking code as data segments (or vice versa), jump tables, self-modifying code, randomization of memory allocation, and interrupts/exceptions. The goal is to perform the normal software functionality and protection code in a convoluted way that makes it difficult to understand or reliably modify the program flow. Typically, obfuscation is done at the assembly language level after the main software has been compiled although it can be done at other stages also. This transforms the original program P into P’, which should perform the same functions as P but in a very different way.

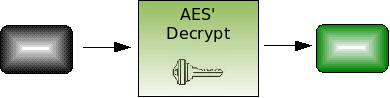

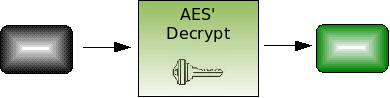

Encryption involves pre-processing code/data in the program with a cipher (e.g., AES, RC4) and then adding a routine to perform the decryption before executing or processing the protected data. Encryption with a standard cipher is theoretically much stronger than obfuscation if the attacker does not have the key. However, the key often needs to be stored in the program or transmitted to the program at some point so it can decrypt the data. At that point, the decrypted data or the key can be grabbed by the attacker.

These two techniques are very different, and it’s important to understand why. Obfuscation, if done properly, has the advantage of having no single point of failure. The code/data is always protected during processing until the attacker carefully unwinds the obfuscation. However, it is often slower than straightforward processing, requires manual intervention to design and insert, and is rarely integrated with the rest of the software protection well enough that an attacker can’t just go around it. Encryption offers strong theoretical security, but has a single point of failure: the key. If the key is not present in the software (i.e., a PIN to unlock add-on features), encryption offers very strong protection. However, often weak encryption like XOR is used or the key is not protected very well when stored in the program itself.

The best approach is to combine obfuscation and encryption, along with all the other techniques, offsetting the weaknesses of each with the strengths of the others. For example, the traditional approach to implementing software decryption would be to take a stock C implementation of AES and call it with the key and a flag indicating it should perform decryption.

The weakness here is that the key is stored separately from the decryption routine and thus may be easy to isolate and extract. Since this function is not being used for encryption or with different sets of keys, it makes sense to combine the key and cipher implementation into a single primitive: an obfuscated hard-coded decryption function.

One approach is to take a set of random bijections and combine it with the key and cipher to produce this fixed decryption function. Specifically, each component of the cipher is replaced with an equivalent, randomized function that computes one stage of the decryption using the fixed key. This is possible because block ciphers are composed of a number of small functions (substitute, permute or shuffle around, add key material), run over and over for a number of rounds. As long as each modified function still produces the correct results for the fixed key and variable data, the combination of them will still compute the same result as stock AES. (More details on this technique, called “white-box cryptography,” can be found in these papers on DES and AES.)

Of course, if an attacker can just isolate and enslave this decryption function to recover arbitrary data from the program, it isn’t very effective. That’s why other techniques are needed to tie the decryption function to the entire software protection.

Next, we’ll cover anti-debugging and anti-tampering techniques.